Nothing Ventured, Millions Gained

05/22/2003 — S V Dáte, Palm Beach Post

Imagine the state gave you $75 million in tax money to invest in new businesses to create jobs.

Imagine that, rather than creating jobs, the companies you invested in lost 174 jobs in the first four years. Imagine you got to keep all the money anyway, without ever having risked a penny of your own.

Sound too good to be true?

For three venture capital firms, it's all true but still not good enough. They are pressing for a second round of tax credits to get as much as $75 million more among them.

One, New Orleans-based Advantage Capital Partners, which wrote the law creating the program in 1998, actually has threatened Gov. Jeb Bush with a lawsuit if the money isn't forthcoming.

"I believe that it is very likely that we will prevail in court (I would put our chances at 70-30)," Advantage managing director Maurice Doyle, who is a lawyer, wrote in a May 9 e-mail to lobbyist Mike Harrell that Harrell forwarded to Bush on May 12. "If a lawsuit is our only recourse, we will pursue it aggressively."

The suit would stem from the legislature's creation of a second phase of tax credits last spring but its failure to pay for them.

After threatening the lawsuit, Doyle's e-mail then proposed a plan for Bush to start phase two immediately but delay the additional tax credits to pay for it for five years.

"The governor will benefit from, and can take credit for, the economic stimulus that is generated from our investments. However, the governor will be out of office (due to term limits) by the time that the fiscal impact is recognized," Doyle wrote.

Bush responded to Harrell, a frequent golfing buddy, three hours later with a single line: "I will look into it."

Bush said Wednesday he is reluctant to expand the program before seeing how it does over a longer period of time. As for anything occurring this year: "I don't think it's going to happen."

Other lobbyists for the companies have been trying to sneak language that would get them the money into the budget "implementing bill" that must be passed for the state's $52 billion budget to take effect July 1.

However, the Senate, which Doyle blames in his note for being "unwilling to help us," seems set in its opposition.

"It just isn't going to happen," said Senate budget Chairman Ken Pruitt, R-Port St. Lucie, who met with representatives of the three companies Monday morning.

Complicated mechanics

Called the "CAPCO" -- for "capital company" -- tax credit, the program originally was slipped through both chambers by two prominent lawmakers on behalf of Advantage Capital Partners, which was represented by prominent GOP lobbyist and bill author Pete Dunbar.

Dunbar got his close friend, former Senate Majority Leader Jack Latvala, R-Palm Harbor, to push the measure in that chamber and former Rep. Tom Feeney, R-Oviedo, to push it in the House. The bill failed in 1997 but passed in 1998. Former Gov. Lawton Chiles allowed it to become law without his signature.

Latvala did not return phone calls, and Feeney, now in Congress, refused to answer questions. Chiles died in December 1998.

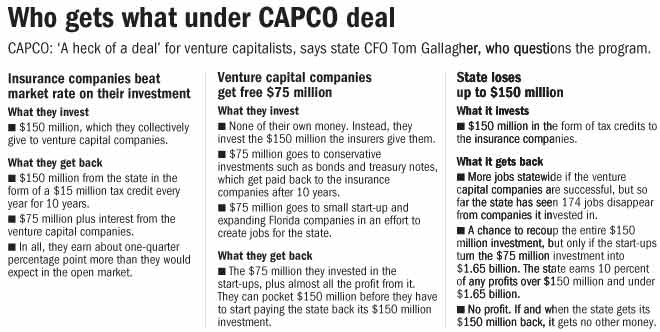

The program works through a complicated scheme. Insurance companies give venture capital firms $150 million to invest. In return, the state gives the insurance companies $150 million in tax credits over 10 years. The venture capitalists sink as much as half of the money in safe investments to pay back the insurance companies, with the rest going into small and start-up Florida businesses.

Critics of CAPCO, however, call the whole insurance company involvement nothing more than a shell game designed to obfuscate the program's true goal: to put tens of millions of taxpayer dollars into the pockets of a few venture capitalists.

Indeed, after setting aside as much as $75 million to pay back the sponsoring insurance companies, the venture capital firms are free to keep the other $75 million, as long as they invest it and reinvest it in the small Florida businesses, as specified in the law, over a period of years.

Investments push profits

Once those conditions are met, the investments belong to the capital company, the law states. If the investments grow, so do the firm's profits. The law, in fact, allows a firm's total profit to equal the original amount it received in tax credit proceeds before the state shares in a single dime.

Advantage Capital, for example, would have to see the $41 million it originally set aside for venture capital investing grow to $81.8 million before it would have to share profits with the state. Even when that threshold is reached, the firms must give the state treasury only 10 percent of every dollar they earn beyond that, a share that stops when the state has recouped the amount of the original tax credits.

Thus Advantage would have to give Florida 10 cents for every dollar its investments earn above $81.8 million. The state would recoup the $81.8 million it gave to Advantage only in the event the investments grow 22-fold and hit $900 million.

In contrast, a traditional institutional investor that placed $81.8 million with a venture capital firm would pay only a 2.5 percent annual management fee until the investments reached the original value, and would then receive 80 percent of the profits thereafter. If the portfolio value ever grew to $900 million, the investor's share would be $716 million.

"It's a heck of a deal," said state Chief Financial Officer Tom Gallagher. "I think it's terrible public policy. We've got a lot more needs in this state than funding venture capitalists."

Traditional tack unchecked

CAPCO program supporters never looked into setting up a traditional venture capital program within state government -- similar to the State Board of Administration, for example, which invests the state's $100 billion pension fund.

Critics charge that the driving force behind the idea, Advantage Capital, stood to make $100 million or more using the insurance tax credit method and only $10 million to $20 million if the company merely administered a state-run investment program.

Tate Garrett, the 39-year-old senior vice president who runs Advantage's Florida office in Tampa, concedes that the program could mean upwards of $60 million in his and his associates' pockets, even if Advantage winds up investing poorly and their companies lose money.

"I agree it's a good deal for us. But I think it's a good deal for the state, too," he said.

Advantage has built its $600 million business entirely on state-subsidized CAPCO programs around the country, Garrett said. It pushed lawmakers in Louisiana to create the first one. Missouri, Florida, Wisconsin, New York and Colorado have followed. Advantage participates in them all and plans to participate in new ones in Alabama and Georgia, Garrett said.

Garrett and Dunbar say an alternative idea, in which the state would contract with a venture capital company as a traditional institutional investor, was never considered. It would have cost Florida $75 million less up front and potentially provided tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue -- an impossibility under the existing framework.

Dunbar, who agreed he was working on Advantage's behalf when he wrote and pushed the legislation, defended the payout that Advantage's handful of partners could receive, saying they are all highly educated businessmen with advanced degrees.

"What do you want them do to?" he said. "Waste their time, and get nothing at the end?"

2 other firms get part

When Florida's law passed in 1998, Advantage sought the entire $150 million by signing up 35 insurance companies pledging between $500,000 and $15 million each for the tax credits.

Bush's office, however, awarded two other venture capital companies portions of the total. Advantage Capital received $81.8 million; New York-based Wilshire Partners, $37.4 million; and Ohio-based Stonehenge Capital, $30.8 million.

By the end of 2001, the companies' investments collectively accounted for a net total of six new jobs across 28 companies -- none of which was in enterprise zones, urban high crime areas, rural job tax credit counties, nationally recognized historic districts or the so-called "Front Porch" communities that the law called for the investments to favor.

That performance did not prevent Latvala from inserting a doubling of the program to a total of $300 million into a bill last May that merged the comptroller's and the insurance commissioner's offices. The 2002 CAPCO language, however, contained the phrase "appropriated by the legislature" when it referred to the second $150 million. Proponents did not realize then that the state would interpret those words as meaning that the legislature would have to allocate the money specifically.

Advantage Capital and its lobbyists have been trying to undo those four words all spring.

"That word 'appropriated' has hung us up big time," Garrett said, adding that state officials are taking advantage of the word to stop a program merely because they do not want to spend another $15 million a year.

"We can just slug it out in court," Dunbar said.

On March 14, Bush's budget director, Donna Arduin, wrote Pruitt and his House counterpart, Rep. Bruce Kyle, for "additional explanation and direction" about CAPCO's Program Two: "What is the total dollar amount appropriated by the legislature for fiscal year 2002-03 for Program Two?"

Pruitt and Kyle wrote back March 17: "There is no current year appropriation for this program."

On April 29, House Deputy Majority Leader Connie Mack, R-Fort Lauderdale, tried to slip wording into an unrelated bill that would delete the words "appropriated by the legislature," but he later withdrew the amendment. He did not return phone calls for comment. In a year when money is so tight that the allocation for children's textbooks may be slashed, supporters will have a tough time explaining the need for further subsidizing venture capitalists.

Bush's office has not finished its report on the program for 2002, even though state law requires one by April 1. However, an analysis prepared by Advantage's Garrett shows that, since the program began, CAPCO has resulted in the net loss of 174 jobs. The 30 companies the three venture capital firms invested in began with 773 jobs. On Dec. 31, 2002, that figure was down to 559.

Both Dunbar and Garrett question the use of those figures by Bush's office. Dunbar said the job loss might have been even worse had it not been for the venture capital firms' investments.

And Garrett said it is not fair to count job losses in a company as a negative number. If a company he invested in started with five employees but then went bankrupt, the number of jobs created for it should be zero, not negative five, he said.

He pointed to one company that lost four positions. "They're charging that my $2 million investment destroyed four jobs," he said. "It's ludicrous."